Don't Blink - Robert Frank

Robert Frank revolutionised photography and independent film. He documented the Beats, Welsh coal miners, Peruvian Indians, The Stones, London bankers, and the Americans. This is the bumpy ride, revealed with unblinking honesty by the reclusive artist himself.

| Director | Laura Israel |

| Actors | Jean-Philippe Desrochers, Jean-Philippe Desrochers |

| Share on |

In the introduction he wrote for the U.S. edition of The Americans (1959), Jack Kerouac described his friend Robert Frank’s legendary book as “a sad poem right out of America onto film,” allowing the photographer to join “the tragic poets of the world.”

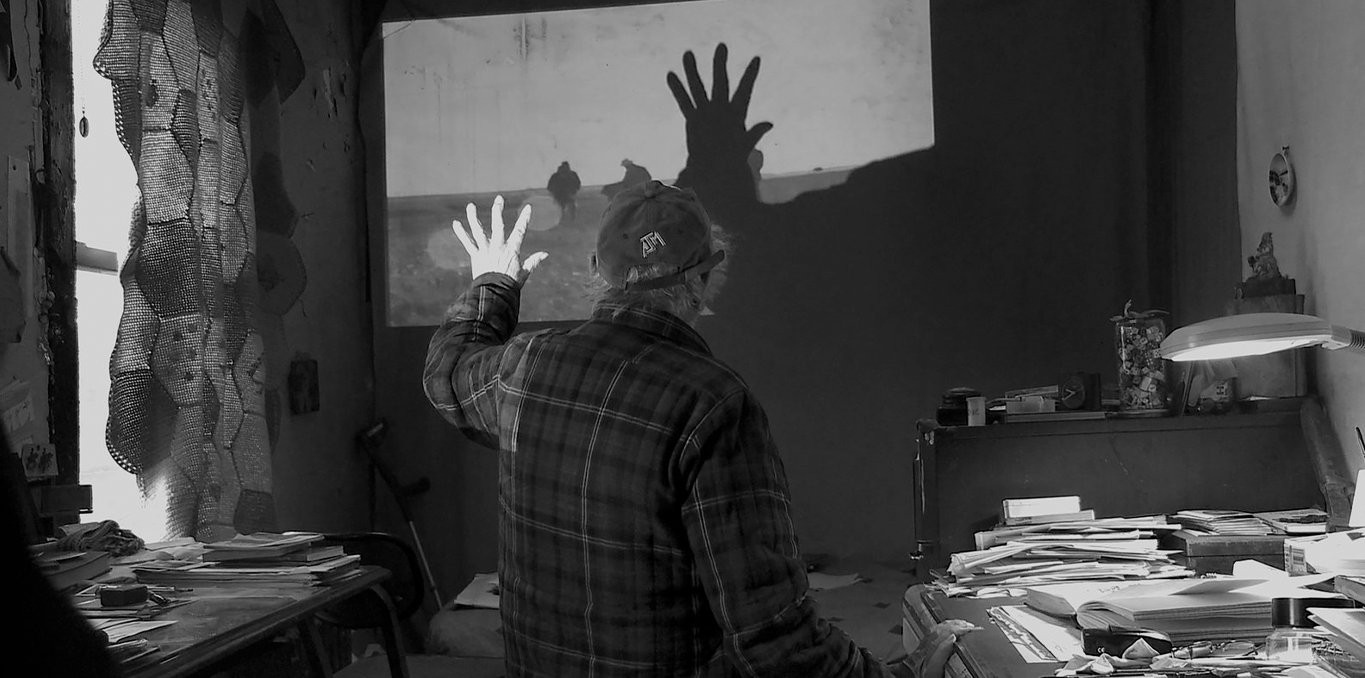

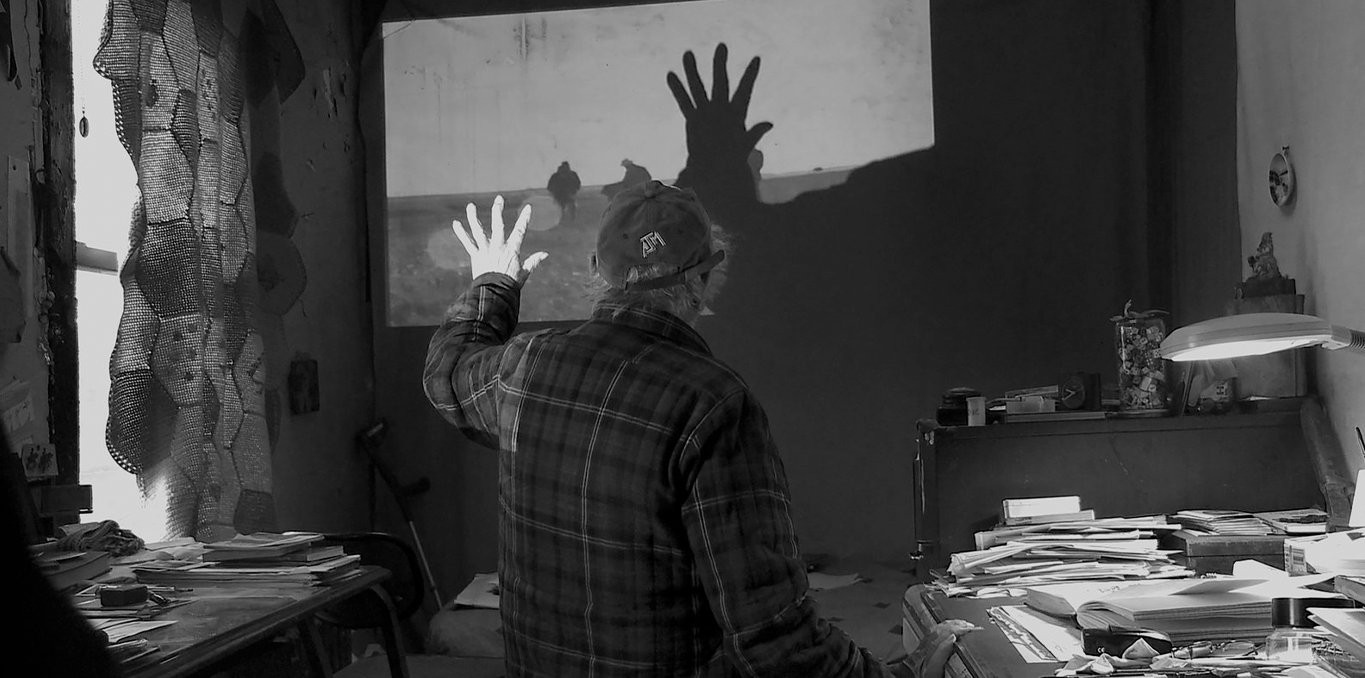

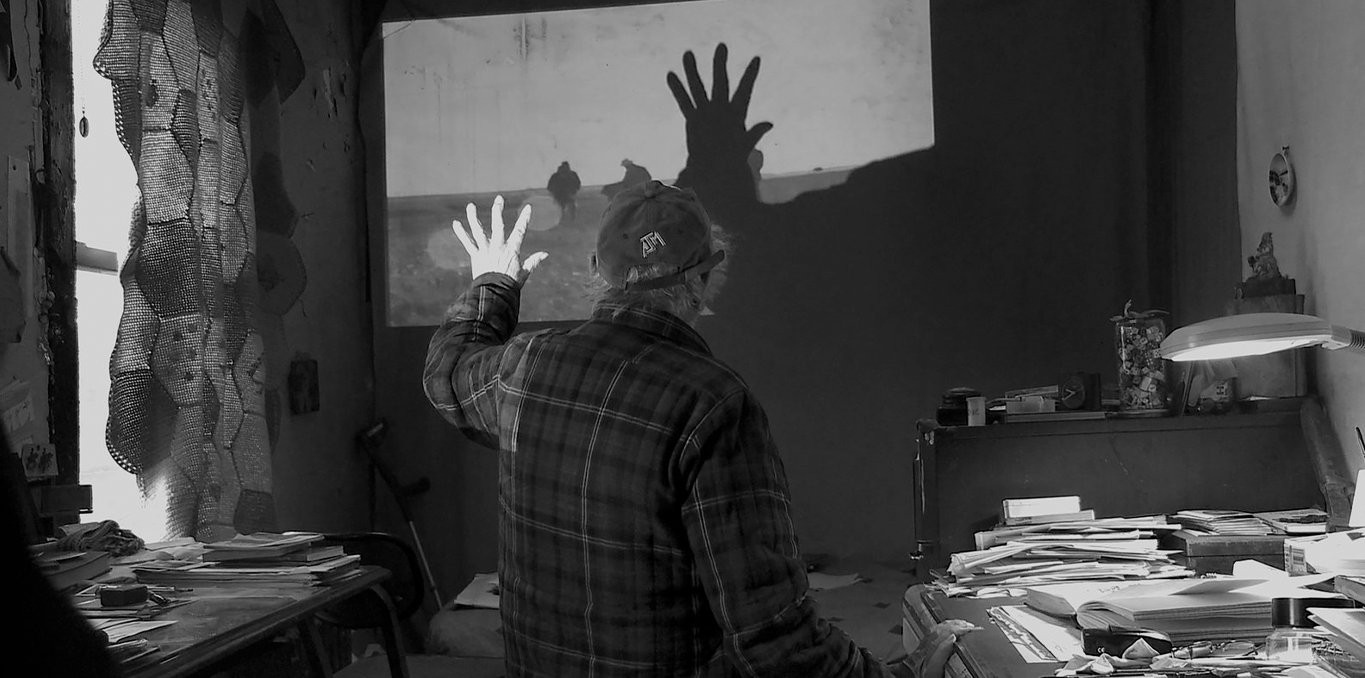

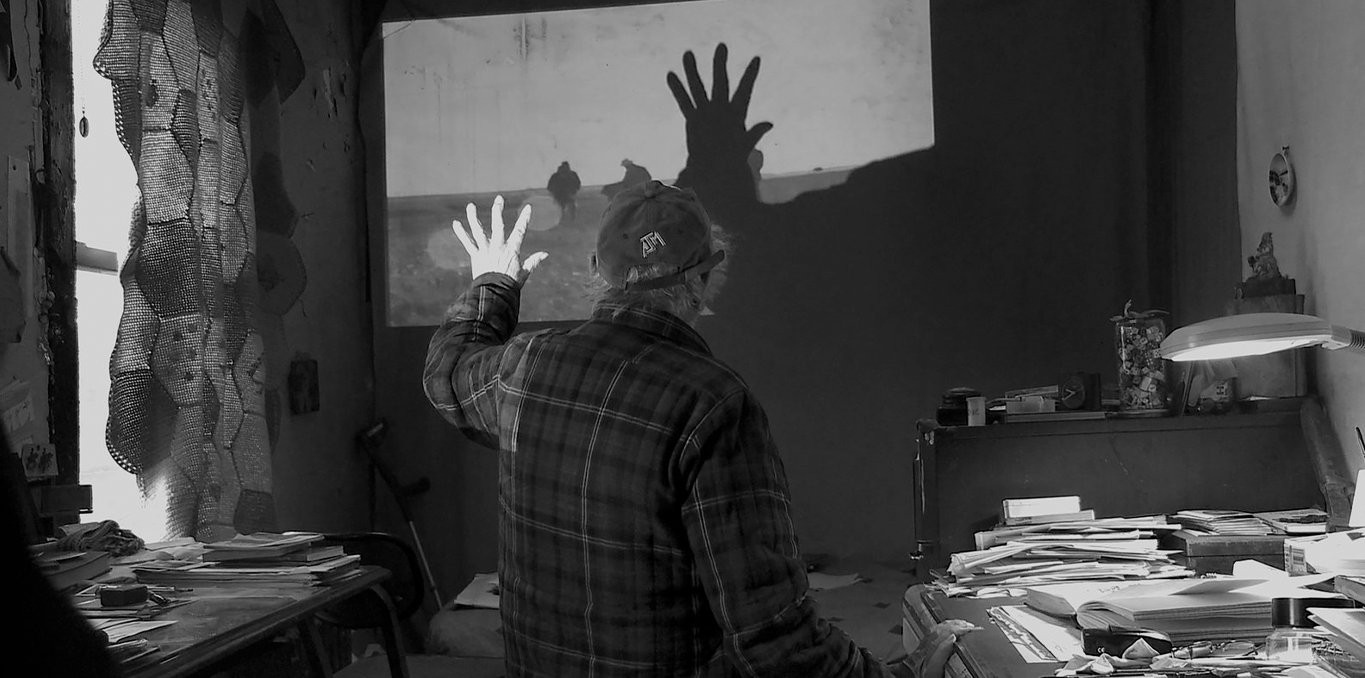

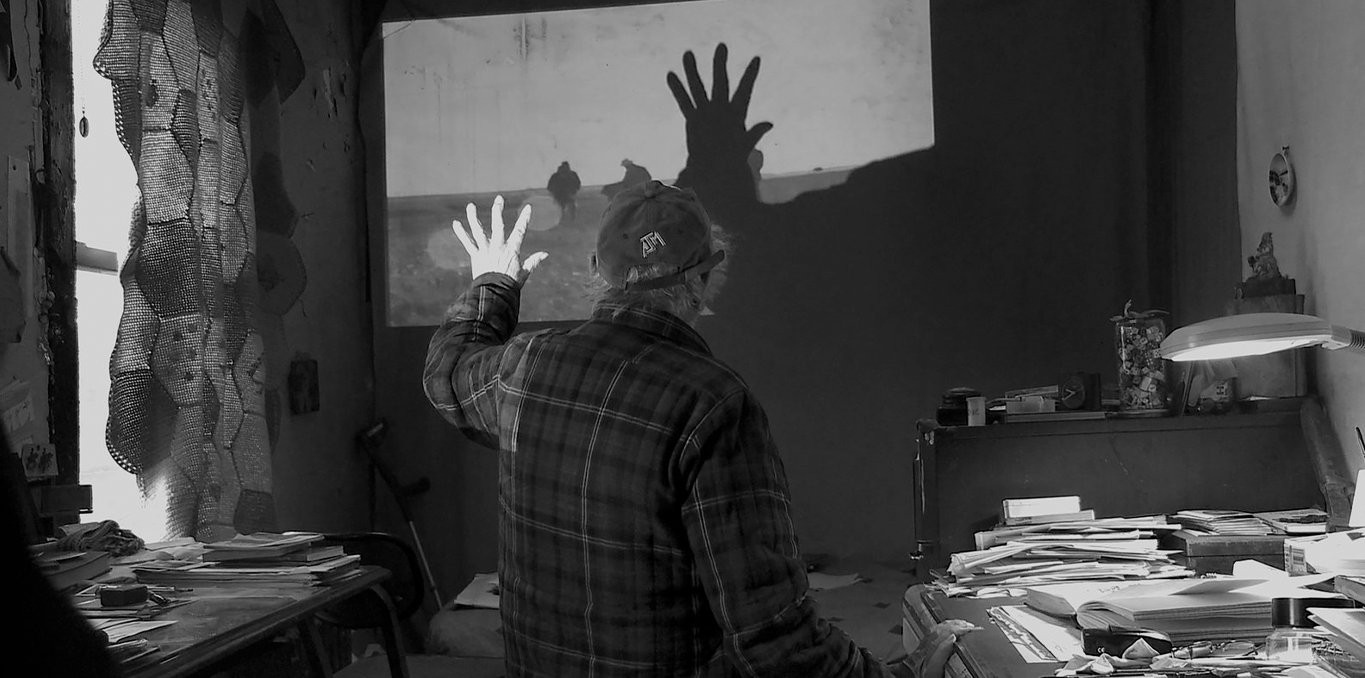

At the beginning of the documentary Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank (Gerald Fox, 2005), we see the artist, temperamental and impatient, asserting that Fox’s interview lacks spontaneity. Ten years later, in Don’t Blink, Laura Israel approaches the solitary, cantankerous elder with much more tact. Well acquainted with Frank, having edited several of his films, Israel does not however soften reality. She structures her film around an archival video from 1984, in which Frank appears particularly annoyed by the questions posed to him, trapped within the frame—both of the camera and of the interview—from which he declares he wants to escape. Yet, in Israel’s presence, he willingly speaks about his work, whether his photographic oeuvre or his deeply personal documentaries.

The punk tone of Don’t Blink is established from the outset, as an energetic piece by The Mekons accompanies a tight, dynamic montage of Frank’s photographs. The rest of the documentary is punctuated by songs from musicians whose worlds clearly resonate with Frank’s, including Tom Waits, The Velvet Underground, Bob Dylan, and Patti Smith. Alternating between Frank’s New York studio and his modest home in Mabou, Nova Scotia—where he also reflects on his friendship with Gilles Groulx—the film gently addresses the tragedies that have marked his life. A true visual and sonic feast, Don’t Blink delves deeply into Frank’s iconoclastic work and brilliantly captures the mindset of the eternal rebel he always was.

Jean-Philippe Desrochers

Critic

-

Français

1h22

Language: Français

Subtitles: Français -

English

1h22

Language: English

- Année 2015

- Pays United States, Canada, France

- Durée 82

- Producteur Assemblage Films, ARTE

- Langue English

- Sous-titres French

- Résumé court An intimate portrait of Robert Frank, capturing the inseparable life and work of the photographer and filmmaker who continues to reinvent himself with unflinching curiosity.

- Ordre 4

- TLF_Applismb_CA 1

- Date édito CA 2025-10-31

In the introduction he wrote for the U.S. edition of The Americans (1959), Jack Kerouac described his friend Robert Frank’s legendary book as “a sad poem right out of America onto film,” allowing the photographer to join “the tragic poets of the world.”

At the beginning of the documentary Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank (Gerald Fox, 2005), we see the artist, temperamental and impatient, asserting that Fox’s interview lacks spontaneity. Ten years later, in Don’t Blink, Laura Israel approaches the solitary, cantankerous elder with much more tact. Well acquainted with Frank, having edited several of his films, Israel does not however soften reality. She structures her film around an archival video from 1984, in which Frank appears particularly annoyed by the questions posed to him, trapped within the frame—both of the camera and of the interview—from which he declares he wants to escape. Yet, in Israel’s presence, he willingly speaks about his work, whether his photographic oeuvre or his deeply personal documentaries.

The punk tone of Don’t Blink is established from the outset, as an energetic piece by The Mekons accompanies a tight, dynamic montage of Frank’s photographs. The rest of the documentary is punctuated by songs from musicians whose worlds clearly resonate with Frank’s, including Tom Waits, The Velvet Underground, Bob Dylan, and Patti Smith. Alternating between Frank’s New York studio and his modest home in Mabou, Nova Scotia—where he also reflects on his friendship with Gilles Groulx—the film gently addresses the tragedies that have marked his life. A true visual and sonic feast, Don’t Blink delves deeply into Frank’s iconoclastic work and brilliantly captures the mindset of the eternal rebel he always was.

Jean-Philippe Desrochers

Critic

-

Français

Duration: 1h22Language: Français

Subtitles: Français1h22 -

English

Duration: 1h22Language: English1h22

- Année 2015

- Pays United States, Canada, France

- Durée 82

- Producteur Assemblage Films, ARTE

- Langue English

- Sous-titres French

- Résumé court An intimate portrait of Robert Frank, capturing the inseparable life and work of the photographer and filmmaker who continues to reinvent himself with unflinching curiosity.

- Ordre 4

- TLF_Applismb_CA 1

- Date édito CA 2025-10-31