For a Few Lives

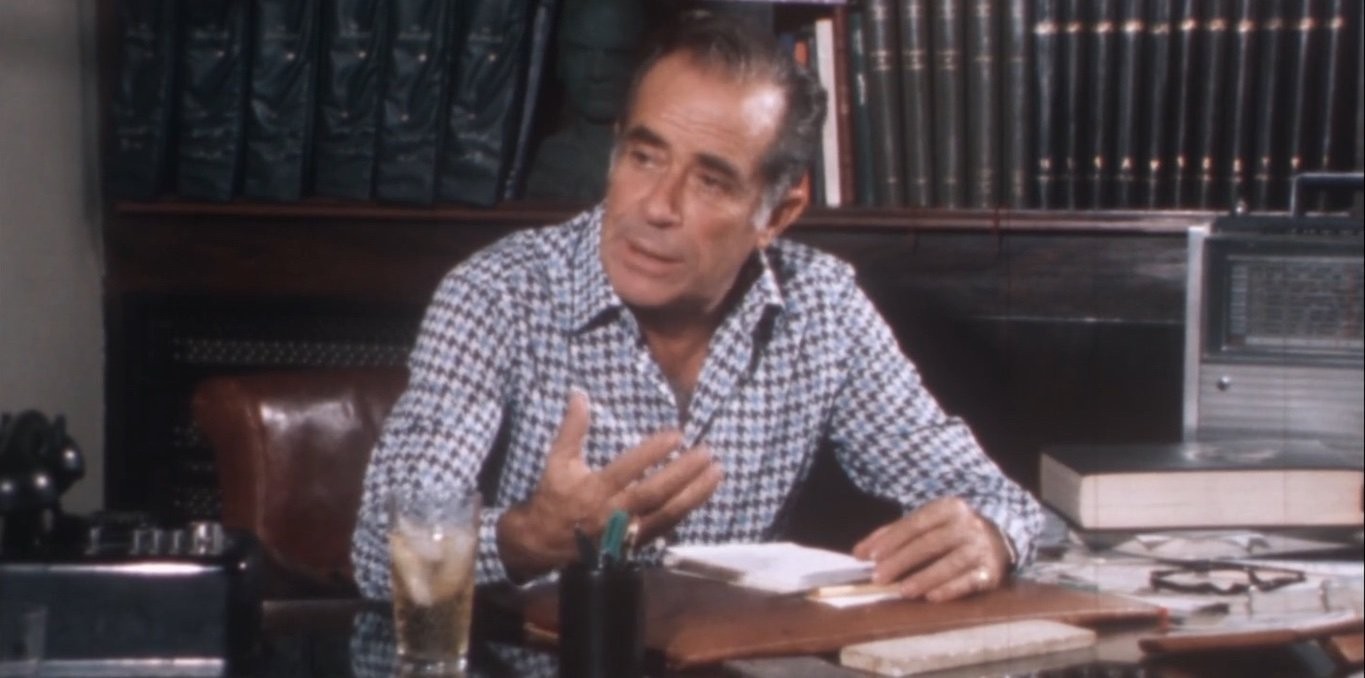

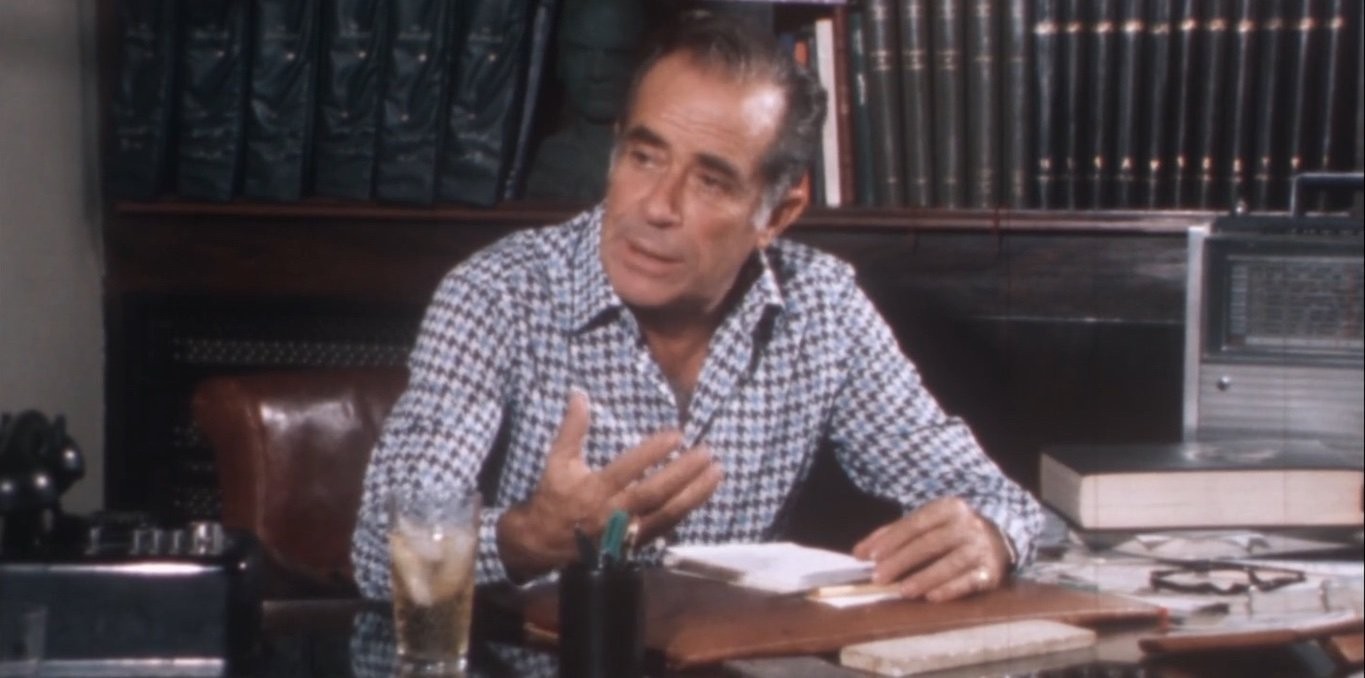

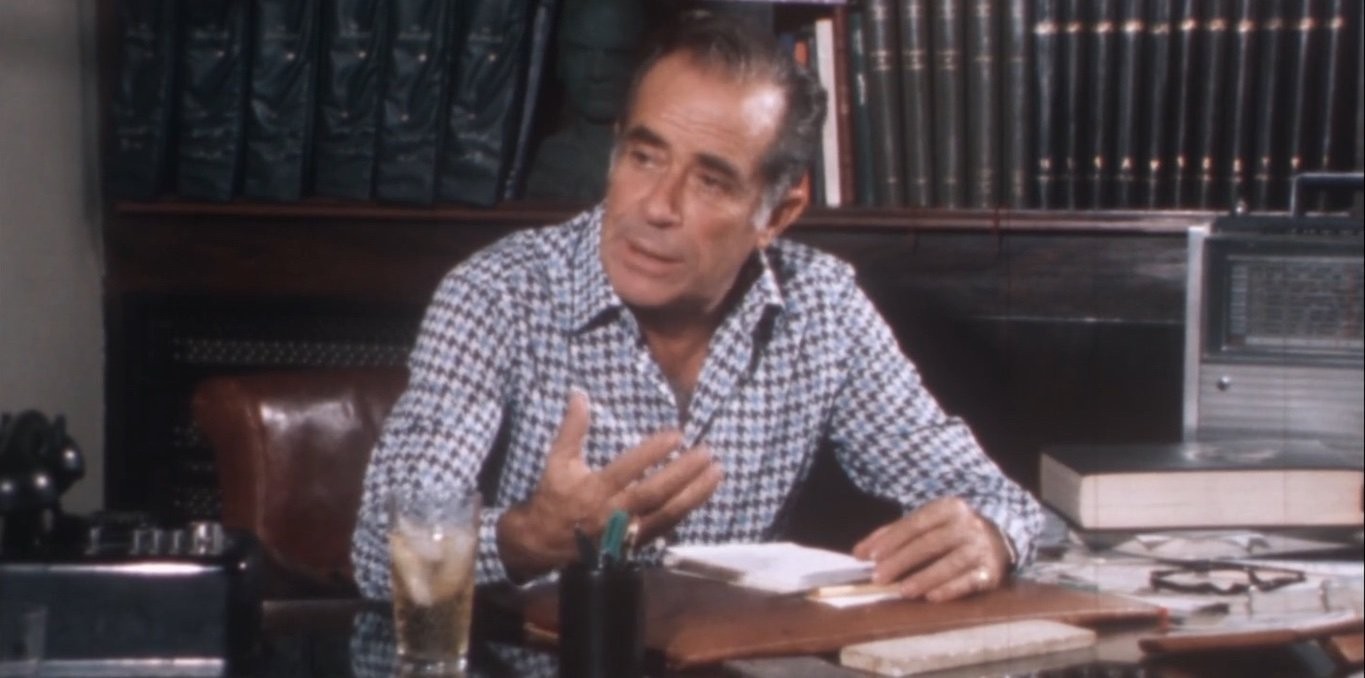

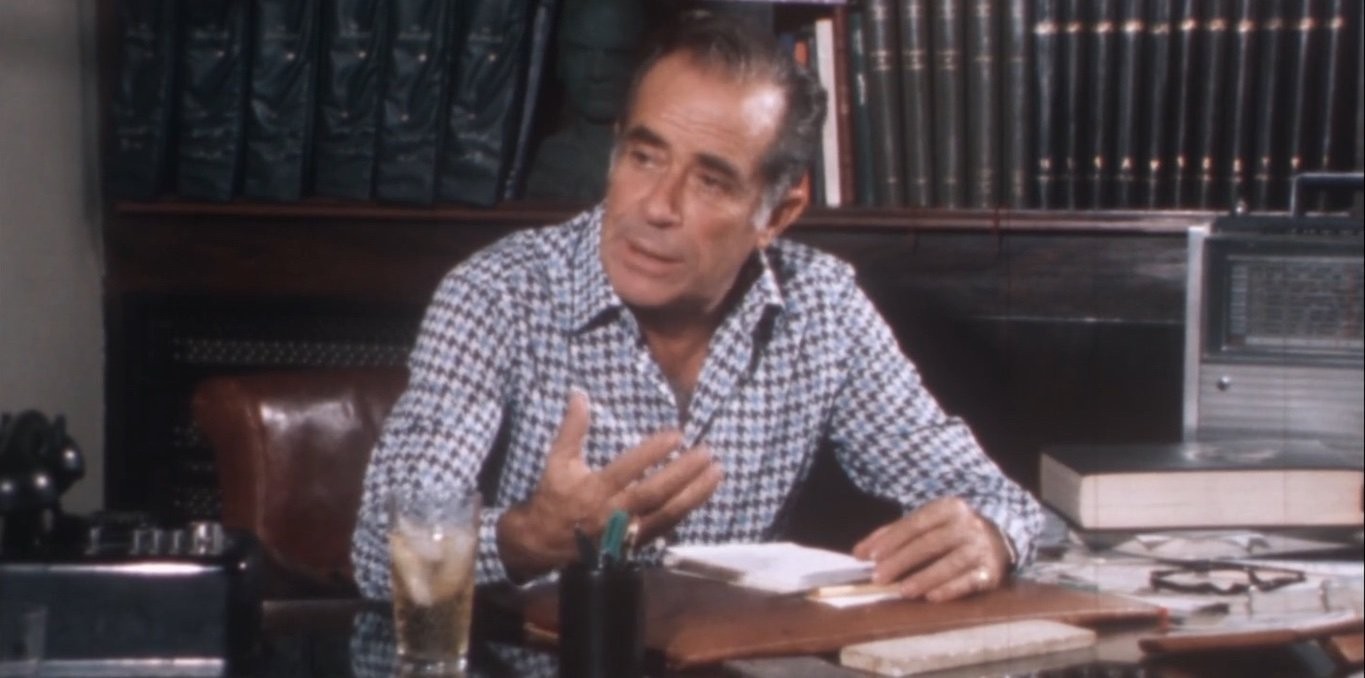

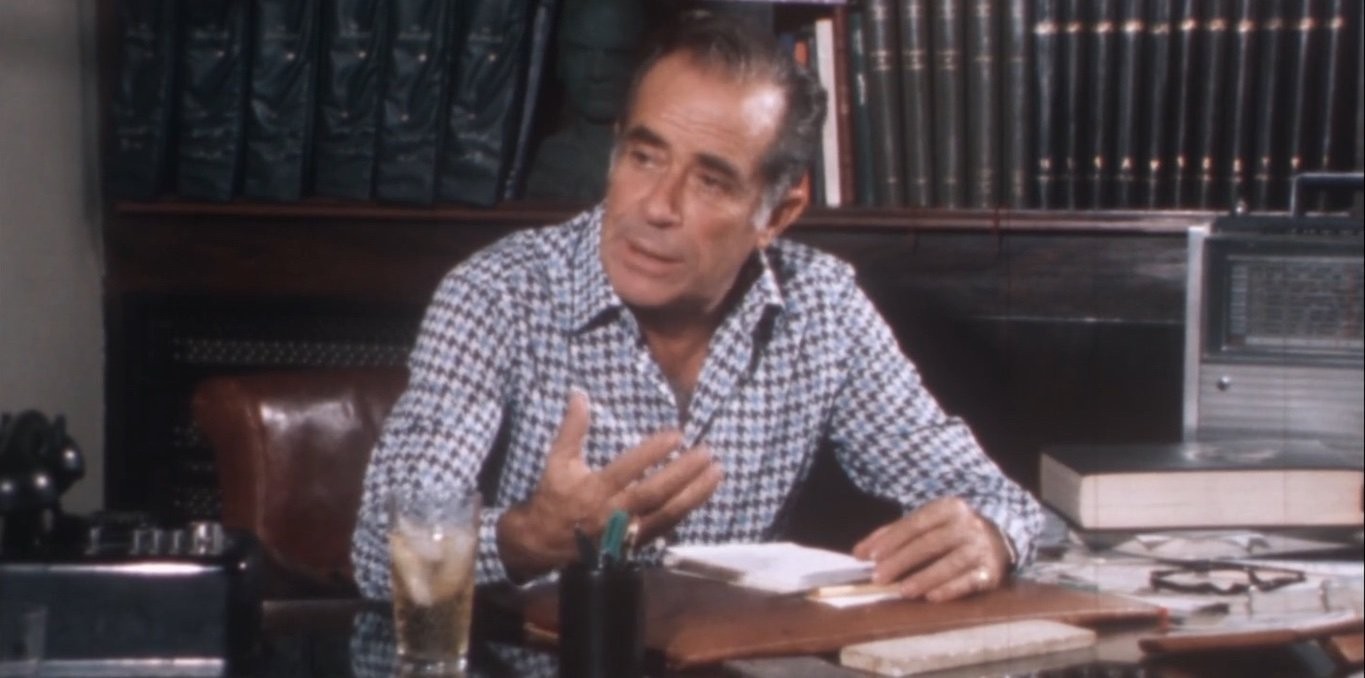

Portrait of Raymond Eddé, a candidate in the Lebanese presidential elections and a staunch opponent of the sectarian war. During the 1975–1976 conflicts, he and his team actively searched for those who had gone missing in the war, whether Christian, Druze, or Muslim.

| Director | Jocelyne Saab |

| Actors | Naomie Décarie-Daigneault, Naomie Décarie-Daigneault |

| Share on |

For a Few Lives (1976) by Jocelyne Saab is a tense, political, and intimate chamber piece. Saab follows Raymond Eddé, a Lebanese presidential candidate who stands as a figure of integrity. In the midst of the chaos of 1975–1976, he searches for the missing persons, whoever they may be: Christians, Muslims, Druze. Saab attempts to film a “righteous man,” or what remains of one, in a country stripped of its bearings. It is a desperate yet clear-eyed quest, an attempt at redemption in the face of a collective morality in total collapse. This is not an action film, but a film of gestures, of waiting, of faces, and of the dead restored to their dignity. What matters here is the trace, the memory, the attempt to save a few lives—or at least their names. Saab captures the war without ever showing it head-on, letting it resonate in the silence of absent bodies.

What strikes me first is the voice-over, which immediately transports me back to my childhood. In these voices from wartime documentaries, there is a very specific intonation, typical of francophone journalism of the era: a way of pronouncing, of narrating, that activates multiple layers of memory and awakens an intimate echo in each of us. This voice-over embodies all the stories of collapse.

Chantal Partamian

Filmmaker and archivist

-

Français

18 mn

Language: Français

Subtitles: Français -

English

18 mn

Language: English

Subtitles: English

- Année 1976

- Pays Lebanon, France

- Durée 18

- Producteur Jocelyne Saab

- Langue French, Arab

- Sous-titres English, French

- Résumé court An immersion with Raymond Eddé and his team as they investigate to locate those missing from the Lebanese Civil War, regardless of religious affiliation.

- Ordre 3

- Capsule film <p>Continue exploring the work of Jocelyne Saab through original complementary resources created by <a href="https://zoom-out.ca/filter/tag/jocelyne-saab" target="_blank"><span style="color:#008080;"><u><strong><em>Zoom Out</em></strong></u></span></a> for the occasion of the first partial retrospective of the filmmaker’s newly restored films, presented at the Cinémathèque québécoise from May 18 to 25, 2022.</p>

- TLF_Applismb_CA 1

- Date édito CA 2025-01-31

For a Few Lives (1976) by Jocelyne Saab is a tense, political, and intimate chamber piece. Saab follows Raymond Eddé, a Lebanese presidential candidate who stands as a figure of integrity. In the midst of the chaos of 1975–1976, he searches for the missing persons, whoever they may be: Christians, Muslims, Druze. Saab attempts to film a “righteous man,” or what remains of one, in a country stripped of its bearings. It is a desperate yet clear-eyed quest, an attempt at redemption in the face of a collective morality in total collapse. This is not an action film, but a film of gestures, of waiting, of faces, and of the dead restored to their dignity. What matters here is the trace, the memory, the attempt to save a few lives—or at least their names. Saab captures the war without ever showing it head-on, letting it resonate in the silence of absent bodies.

What strikes me first is the voice-over, which immediately transports me back to my childhood. In these voices from wartime documentaries, there is a very specific intonation, typical of francophone journalism of the era: a way of pronouncing, of narrating, that activates multiple layers of memory and awakens an intimate echo in each of us. This voice-over embodies all the stories of collapse.

Chantal Partamian

Filmmaker and archivist

-

Français

Duration: 18 minutesLanguage: Français

Subtitles: Français18 mn -

English

Duration: 18 minutesLanguage: English

Subtitles: English18 mn

- Année 1976

- Pays Lebanon, France

- Durée 18

- Producteur Jocelyne Saab

- Langue French, Arab

- Sous-titres English, French

- Résumé court An immersion with Raymond Eddé and his team as they investigate to locate those missing from the Lebanese Civil War, regardless of religious affiliation.

- Ordre 3

- Capsule film <p>Continue exploring the work of Jocelyne Saab through original complementary resources created by <a href="https://zoom-out.ca/filter/tag/jocelyne-saab" target="_blank"><span style="color:#008080;"><u><strong><em>Zoom Out</em></strong></u></span></a> for the occasion of the first partial retrospective of the filmmaker’s newly restored films, presented at the Cinémathèque québécoise from May 18 to 25, 2022.</p>

- TLF_Applismb_CA 1

- Date édito CA 2025-01-31